Readers of a certain age will be familiar with “A Shot in the Dark”, a comedy caper starring Peter Sellars that was part of the Pink Panther series in the ‘60s and ‘70s. It may seem unlikely starting point for a blog about the European Commission’s efforts to combat fraud, but that was what sprang to mind when reading the recent report by the European Court of Auditors: “Fighting Fraud in EU Spending: Action Needed”.

It is not that the image of Peter Sellars’ hapless Clouseau character comes to mind when reading the report’s criticisms of the European Anti-Fraud Office, the unfortunately acronym-ed OLAF. That would be much too unkind to an institution that has the thankless task of being the first line of defence against fraud and corruption in EU funds, without being given anything like the tools it needs to do the job properly, such as powers to compel suspects to give evidence or to prosecute cases in national courts. That deficiency has long been recognised and the new European Public Prosecutors’ Office that is being set up will go some way to plugging that gap.

Rather, it’s that the Commission has only the vaguest idea of the real fraud and corruption risks it faces. As one would expect of a mature bureaucracy, it has an impressive battery of anti-fraud policies and procedures. Whether any of this is adequate or effective however is anyone’s guess. The best efforts of Commission auditors, investigators and anti-fraud experts may be hitting the target… or may not.

The main charge levied against OLAF and the Commission is that they rely on an inadequate measure of fraud and fraud risk – “detected fraud” – which is simply those cases of fraud involving EU funds that Member States report back to the Commission. Quite apart from the incentives for Member States to under-report, there are a number of practical and methodological objections to using this as your baseline measure of risk. No other external sources are used. But it is on this basis that five of the seven Commission spending departments reviewed declared that the risk of fraud is ‘low’. This includes DG Regional Policy, which oversees the distribution of €460 billion of cohesion funds in 2014-20, much of it going to large construction projects that are notoriously prone to corruption.

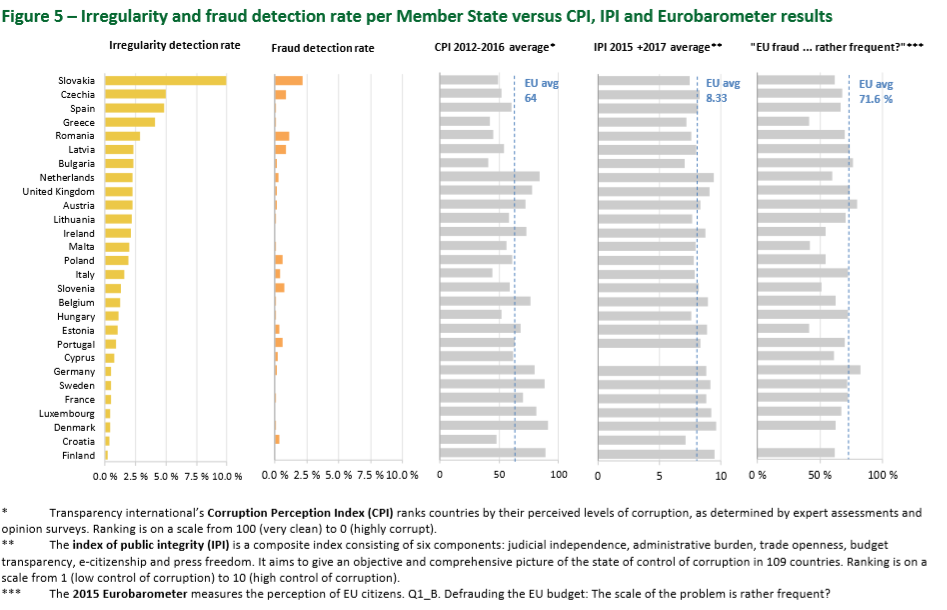

A better measure, says the Court of Auditors, would include estimates of undetected fraud. How to do that? Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is cited, but also tried and trusted criminological methods such as victim surveys. When you compare some of these measures to the Commission’s you get some interesting results (see the table below).

According to the Commission’s ‘fraud detection rate’ indicator – based on self-reporting by Member States, remember – Hungary has one of the lowest fraud rates in the EU, which contrasts with a score of 45 on the CPI, well below the EU average and declining for years amid much evidence of systematic corruption.

In its reply to the report, the Commission is insouciant. It acknowledges the limitations of its own statistics, but claims that getting a better handle on fraud risk would ‘not be proportionate to the cost’, arguing that the cost should not be greater than what the Commission recovers in fraud cases. This seems a peculiar line of argument. Many sources are currently available for free – the CPI, for example, or the Corruption Risk Indicator (CRI) that has been developed specifically for corruption in public contracting by Mihaly Fazekas’s team in Cambridge University – and surely a better and more targeted fraud strategy would lead to more funds being recovered!

The Commission is far from the honey-pot of corruption in populist myth and fantasy. It is fundamentally a decent and well-intentioned institution. As we have pointed out before, however, it does suffer from complacency about corruption risks in particular. And it only takes a few high-profile scandals to make this complacency look like clownish incompetence.