One of the most striking things about the Trump and Farage narratives is the railing against “corrupt elites”: the coalition of “merchant bankers, multinationals and big politics” that Farage invoked when celebrating the Brexit vote; or the swampy and corrupt climate in Congress that was the focus of Trump’s stump speeches. If you put to one side the incongruity of the billionaire and the public school educated stockbroker lining themselves up with the common man against ‘elites’, then the other thing that will strike you about this narrative is how widely it resonates. A poll released last month showed that what Americans fear most is not terrorist attacks or economic collapse but corrupt government officials.

But what is the truth beyond the campaign soundbites and slogans? Today, Transparency International can partly answer that question with the publication of the Europe edition of its 2016 Global Corruption Barometer – a survey of people’s experience and perception of corruption.

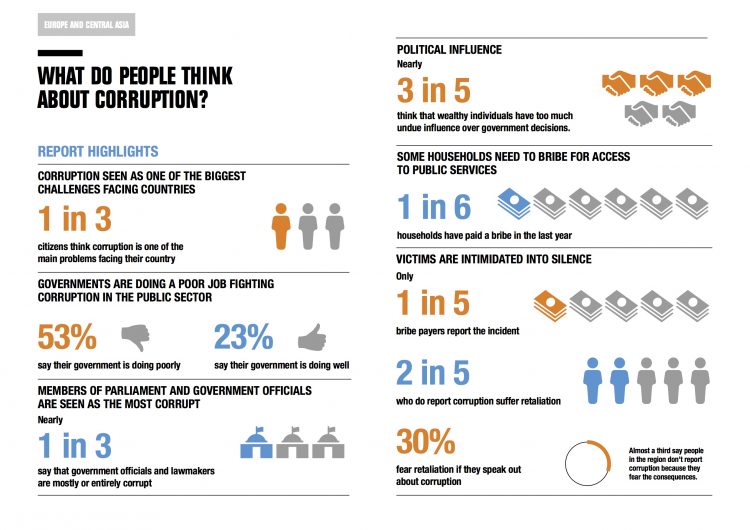

The truth in the EU at least is that people’s direct experience of bribery is relatively limited. Even in Spain where corruption has been top of the political agenda since the financial crisis, the percentage of people reporting paying a bribe when accessing public services such as hospitals, schools, local administration etc. is only 3%. In France and Netherlands, where Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders are currently riding high in the polls on the basis of a similar narrative to Farage, the rate is 2%.

True, as you move further east the reality is less rosy. In Romania, Lithuania and Hungary, more than one in five of people surveyed have paid a bribe for basic services that they should be entitled to as citizens.

And yet corruption consistently features as one of EU citizens’ main concerns in survey after survey. Does this mean that people are deluded about the prevalence and impact of corruption in their societies? Not necessarily. In Spain, for example, the ongoing trial of 37 businessmen and politicians as part of the Gurtel scandal has revealed a ‘kickbacks for contracts’ scheme that thrived for over a decade. No housewives or pensioners were tapped up for a bribe as part of this scheme. Instead, businesses are alleged to have ‘donated’ to political party coffers in return for government contracts.

A victimless crime? Not in the least. The price paid is shoddy public works and a venal political system. This is well understood in Spain and elsewhere and indeed more egalitarian societies seem to be acutely sensitive to this. 65% of citizens surveyed in EU countries believe that the wealthy have too great an influence on politics, an even higher proportion than oligarch-friendly former Soviet states.

The challenge now is to take back the discourse of corruption from nationalist and extremist groups, and for governments and liberal institutions to fashion credible, far-reaching and visible anti-corruption policies. Too often this is farmed out to anti-corruption bureaucrats and obscure agencies. This now needs to be core business.

This might seem a long way from the dull churn of EU policy making, but the EU institutions have suffered most form the ‘unaccountable and corrupt’ brickbats thrown at them by the same nationalist movements. For them it is a question of survival. Here are just some of the ways they can frame a positive agenda:

Empower citizens on the frontline. Our survey shows that over half of the people surveyed in France, Netherlands, Spain and Portugal do not report corruption because of fear of harassment or other reprisals. Across the EU countries surveyed this figures is 35%. In July, The European Commission has tentatively promised to ‘explore’ the possibility of a whistleblower protection directive that would bring national legislation up to international standards. They should bring this legislation forward as quickly as possible

Transparency by default. Citizens who feel remote from the EU are easily misled into believing that multinationals and the wealthy have untrammelled influence on policy makers. The truth is much more nuanced of course, but no-one will believe the bona fides of any one associated with ‘Brussels’. The best option is to pursue a thoroughgoing transparency agenda that leaves no one in any doubt how messy and complicated the whole business is. This means all institutions setting new standards in lobbying transparency, listing all lobby meetings and refusing to meet unregistered lobbyists.

Be visible. The EU, and the European Commission in particular, has a good story to tell about its role in the fight against corruption. It has proposed some ground-breaking transparency legislation, for example the current proposal to end corporate secrecy by making ‘beneficial owners’ of companies publicly available. But it has a woeful track-record of promoting itself as an anti-corruption champion to other governments, let alone citizens. At the UK government’s anti-corruption summit in May, where John Kerry and various heads of state rubbed shoulders, the EU was represented by a Commission Head of Unit. The European Union should join the Open Government Partnership, which would be a good platform for the Commission to showcase its transparency achievements. And a high-level representative joining the OGP Summit in Paris in early December would be a good first step in that direction.