Last week, we took part in the Open Data for Tax Justice design sprint bringing together campaigners, policy experts and open data specialists to discuss the first stages of creating a pilot database for country-by-country reporting (CBCR) data.

Once a database is created we will be able to have a single repository for all existing CBC reports in machine-readable open data format. For the moment only for the banking and extractive sectors, but hopefully soon for all other sectors as well. The most interesting part of all of this though is what this collection of data will help us do, the evidence it will allow us to gather and the stories it will enable us to tell. This is what we tried to do by looking at some of the already existing CBC reports by European banks and here is a first glimpse into what we found:

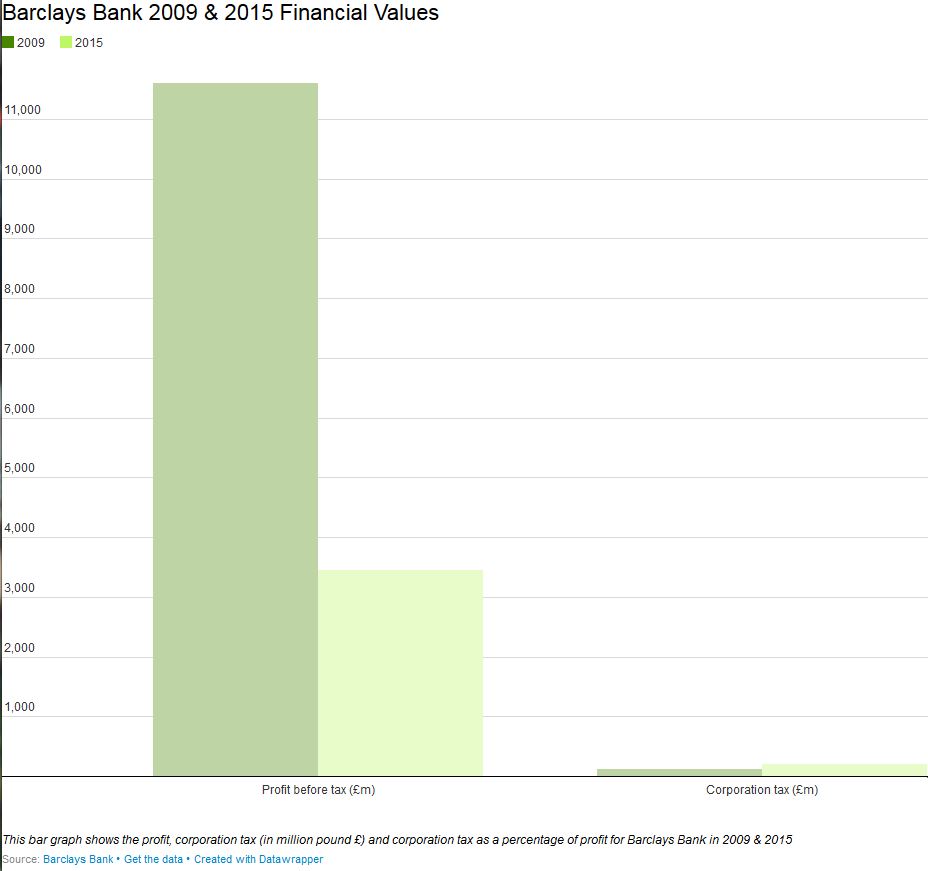

In 2011, an investigation into the tax affairs of several UK multinationals and banks showed how Barclays Bank had made a prolific use of tax havens, in particular the Cayman Islands. What is more, the bank appeared to have avoided huge amounts of tax. It admitted to having paid only 113 million GBP for 11.6 billion GBP of profits made in 2009 – an effective tax rate of 1%, despite the official UK 28% corporate tax rate at that time. The scandal led to strong public outcry against corporate tax avoidance and had massive impacts on the bank’s reputation.

In the wake of this and similar scandals, such as Offshore Leaks, as well as the detrimental impacts of the financial crisis in Europe, in 2013 the European Union (EU) adopted a new piece of legislation – the Capital Requirement Directive IV – which included a measure requiring EU-based banks to publicly disclose some of their key financial data on a country-by-country basis – what is commonly referred to as public country-by-country reporting (CBCR).

Civil society campaigners have advocated for public CBCR for a long time, arguing that it would finally provide citizens with the necessary information to hold multinational companies accountable for their activities, structures and tax payments. The disclosure of financial information, such as turnover, profits, taxes paid, number of employees, among others, with a geographical breakdown for each country of operation of a multinational group or bank will give citizens an indication of the alignments (or misalignments!) of companies’ tax payments and their real economic activity in each jurisdiction.

After the usual implementation phase of the EU directive into the national legal systems of the 28 Member States, in 2016 European banks began publishing their first round of country-by-country reports for data regarding financial year 2015. Fast implementation of the EU legislation in France and the UK meant that French and British banks already started reporting in 2015 ahead of banks from other countries.

We decided to take a look at the first CBC report published by Barclays in 2015 to check whether the situation of their tax affairs and their presence in tax havens had changed since the 2011 tax scandal. The difference between now and then is that now we have access to data that will enable us to tell a story, and no longer need to rely on leaks and investigations.

The first important assessment that we are able to make thanks to the new data is that Barclays has drastically reduced its presence in tax havens, in particular in the Cayman Islands, the Isle of Man and Jersey, where the number of Barclays’ subsidiaries has dropped from 181 to 0, from 30 to 1, and from 38 to 9, respectively. The second assessment is that it seems that Barclays also increased its effective tax rate in the UK compared to 2011. According to its report, it paid 208 million GBP in corporate income tax for 3.4 billion GBP of profits. Of course there is a caveat to this, as corporation tax payable in a given year doesn’t necessarily relate to the profits earned in the same year, as tax on profits is usually paid across multiple years, meaning that it is possible that relatively high corporation tax can be paid when profits are low and vice-versa. This is a loophole in the legislation itself, as it doesn’t require banks to also publish data for their deferred taxes on top of the figures for taxes paid.

Nevertheless, this first look at Barclays’ CBCR data tells us something about the bank’s change of behaviour with regard to its tax policy. Thanks to increased transparency due to mandatory publication of CBCR data, Barclays, as well as many other banks, knows that its tax affairs will be under public scrutiny and has decided to liquidate many of its subsidiaries in tax havens, consequently increasing its tax payments to avoid further reputational damage.

This clearly demonstrates how public CBCR has a strong deterrent function. The fact that banks know that their tax payments are public can help deter them from engaging in questionable tax practices. If banks and companies know that the public is able to scrutinise them, this will affect their decisions and make them re-think how they move money around. To summarise this with the words of an article published last year by the Financial Times, “while transparency might not end the arbitrage, it might at least restore confidence in the process. When it comes to tax morale, a little fiscal voyeurism might do a surprising amount of good.”