By Transparency International Secretariat

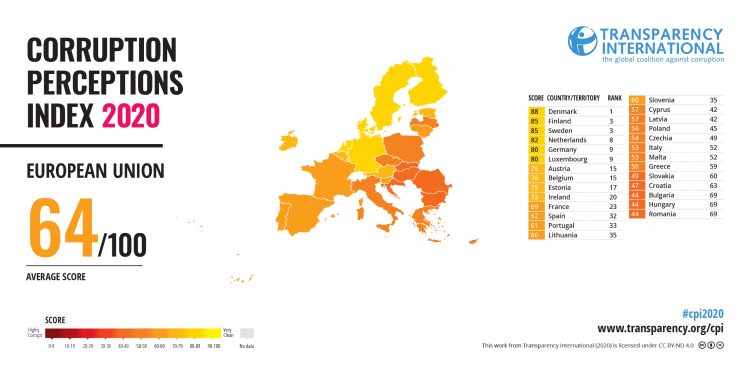

With an average score of 64, the European Union (EU) is among the highest performing regions on the CPI, but is under enormous strain due to COVID-19 and rule of law crises.

Western Europe and the EU score among the highest countries on the CPI, with Denmark (88) hitting the top spot, followed by Finland (85), and Sweden (85). Conversely, the lowest performers from the region are Romania (44), Hungary (44) and Bulgaria (44).

COVID-19 corruption challenges

Across the region, the COVID-19 pandemic has put additional and unexpected pressure on the integrity systems of many countries, making it “a political crisis that threatens the future of liberal democracy”.

The pandemic has tested the limits of Europe’s emergency response, and in many cases, countries have fallen short of full transparency and accountability.

Emergency measures

Following constitutional states of emergency in France (69), Hungary (44), Italy (53) and Spain (62), Democracy Reporting International called out governments for significant human rights restrictions. In addition, due to COVID-19, elections have been delayed in at least 11 EU countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed serious issues related to the rule of law across the region, with corruption further weakening democracies.

Despite these challenges, some countries continue to make progress on the CPI through their anti-corruption efforts.

With a score of 50, Greece is a significant improver on the CPI, jumping 14 points since 2012 and achieving a new high on the CPI, partly as a result of the bold reforms undertaken by the country after 2012 to counter-balance severe austerity measures..

Up next in the EU

For participating EU member states, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office will soon start investigating and prosecuting crimes, though, for the time being, only those committed against the EU budget, like fraud and corruption involving cohesion funds.

An ongoing challenge, very few EU member states have made significant progress in the transposition of the Whistleblower Protection Directive that will take full effect in 2021.

As for assessing the rule of law across the EU, the full effects of a recent report on the topic are yet to be rolled out.

Although an ambitious EU stimulus package could be instrumental to member states’ COVID-19 response, such an initiative is saddled with numerous large procurement processes, subject to strict deadlines and vulnerable to potential corruption and integrity challenges.

Countries to watch

Malta

With a score of 53, Malta is a significant decliner on the CPI, dropping seven points since 2015 and hitting a new all-time low.

According to an EU report about the rule of law in Malta, “deep corruption patterns have been unveiled and have raised a strong public demand for a significantly strengthened capacity to tackle corruption and wider rule of law reforms”.

In 2019, a public inquiry into the murder of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia highlighted high-level corruption and led to the resignation of Prime Minister Joseph Muscat. Muscat.

Muscat’s former chief of staff was arrested in September 2020 for an alleged kickback scheme to help three Russians obtain Maltese passports as part of the controversial golden passports programme in 2015.

In addition, a European Central Bank report found major failings in Malta’s biggest bank, potentially allowing for money laundering and other criminal activities.

Poland

With a score of 56, Poland declines significantly on the CPI, dropping seven points since 2015.

The country’s ruling party has consistently promoted reforms that weaken judicial independence. The steady erosion of the rule of law and democratic oversight has created conditions for corruption to flourish at the highest levels of power.

During COVID-19, the national legislature amended and repealed hundreds of laws, using the crisis as cover to push through dangerous legislation. Parliament also limited access to information for citizens and journalists and allowed opaque public spending related to COVID-19.

An attempt to secure impunity for officials who broke the law in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the heavy-handed police crackdown on peaceful women’s rights protestors increased tensions in the country and revealed the ruling party’s intentions to further solidify its power, despite growing public discontent.

With their recent pushback against the EU for making the rule of law a condition for EU funds, Polish political leaders put democracy and anti-corruption reforms at risk.

Hungary

With an 11 point drop since 2012, Hungary (44) is a significant decliner on the CPI.

Weakening of independent institutions, growing political influence on media and an increasingly hostile environment for civil society, along with corruption scandals involving EU funds had become the country’s new normal even before the pandemic. As the crisis emerged, the ruling party’s two-third majority adopted legal changes further centralising its power and weakening its control of public spending.

Hungary caused serious challenges by threatening to block the adoption of the EU budget and COVID-19 recovery fund. This was an attempt to prevent the final adoption of a political agreement on conditionalities for the protection of the EU budget from breaches of the principles of the rule of law.