The Politics of Overfishing

Fish are a renewable resource: if well managed they can provide sustainable benefits to society in the form of food, revenue and jobs. However, around half of assessed EU stocks in the Atlantic and more than 90% in the Mediterranean are now over-exploited, costing millions in lost revenue and jobs and causing huge ecological damage.

In upcoming negotiations, fisheries ministers from EU Member States will meet to set quotas for 2017. These annual negotiations present an opportunity to stop overfishing and rebuild fish stocks in EU waters. Unfortunately, there is little prospect for this.

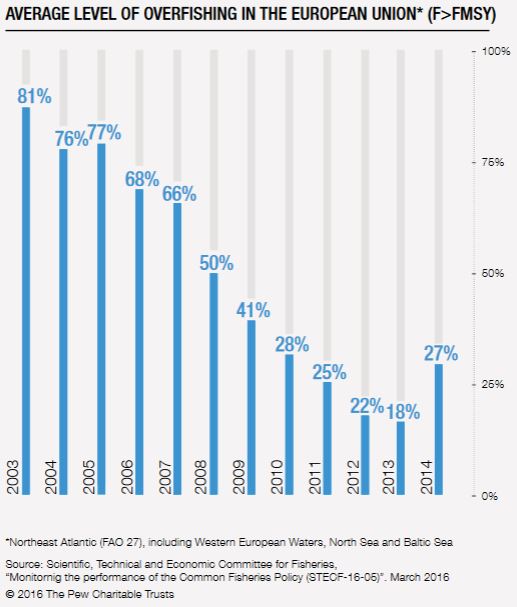

Box 1 – The continuing problem of overfishing in the EU over time

Research, recently published in the Journal of Marine Policy and featured in Nature, shows that while EU ministers head into these negotiations with scientific advice in hand, over the past fifteen years they have set fishing quotas on average 20% above that advice. Although overfishing has declined in the past decade, in the last year for which data is available we have witnessed a worrying reversal of this trend. According to the Commission’s scientific body, STECF, the average level of overfishing for 2014 was 27%.

The problem of overfishing is in part one of an institutional nature. It relates to three different problems arising from the current way EU-level negotiations about fishing are carried out:

- Being a joint-decision as part of a negotiation between 28 national ministers;

- Being a political decision and having to balance different political priorities;

- Being taken in the Council – an institution lacking transparency and public accountability.

Challenge 1: Self-interest and the sustainable management of public goods

Bringing together 28 ministers, representing their Member State interest, and finding agreement is a challenging procedure in itself. What is even more troublesome is that without a third party enforcement body, self-interested agents (the ministers) will get stuck in a so-called “social dilemma”, where what seems rational from an individual perspective creates a situation in which everybody is ultimately worse off: while a single Member State may want to increase its fishing quota for the sake of national interest, overfishing and depleting the overall fish stock is not in the interest of anybody.

Box 2 – Managing public resources and the tragedy of the commons

This intricate situation is well-known in relation to natural resources and has become known as the tragedy of the commons: “a situation within a shared-resource system where individual users acting independently and rationally according to their own self-interest behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting that resource.”

The problem of pushing through narrow special interest at the cost of long-term sustainability can be further aggravated by the undue influence of intensive industry lobbying in advance of the negotiations.

Challenge 2: Long-term sustainability and short-term political decisions

Proponents defending the decisions to allow overfishing usually stress that sustainability of the fish stock is only one among other political dimensions considered, like jobs and survival of the industry. However, in this context, the short-term gains must be balanced against the longer-term costs. The long-term sustainability of fish stocks is vital to secure jobs and maintain profits. In this light, it is in Member States’ social and economic self-interest to manage stocks in a sustainable manner. However, due to the election cycle, there is the risk that politicians do not share this long-term perspective and rather focus on being seen as successful during their mandate.

Challenge 3: Council decision-making and social accountability

Decision-making in the Council has repeatedly been criticised for its lack of real and proactive transparency or a commitment to make meaningful information public in an easily accessible manner. Both are dearly needed to understand what the politically contentious points are and which Member State promotes which position. Under the current Council regime, it is close to impossible for NGOs, the general public, journalists or other stakeholders to hold politicians accountable. Mostly, because they simply don’t know who decided what. The Council, in its function as co-legislator alongside the European Parliament, has been notoriously reluctant to embrace the ‘open government’ and transparency agenda. This is not just compared to the European Parliament, which has been operating under stronger transparency provisions for years – web-streaming most meetings in preparatory stages at committee level, as well as publishing detailed minutes and voting records to allow the public to see which Member of Parliament advocates which policies – but also compared to other national legislators.

How more transparency of Council decision-making can help to end overfishing

There are strong reasons for greater transparency and greater diversity in stakeholder input into the legislative process of Council decision-making as it leads to better policy decisions, better laws and ultimately better outcomes. This principle is enshrined in Article 1 of the Treaty on European Union, which stipulates that “decisions are taken as openly as possible”. Making Council decision-making more transparent is thus not only a question of fundamental principles of the European Union and basic democratic rights of EU citizens, but a transparent legislative process is also the best and easiest way to ensure “better regulation”.

For the special case of Council negotiations on fishing quotas, greater transparency and social accountability would also ultimately help to address the related first two challenges outlined above: the social dilemma of a missing third party enforcement body and the risk of short-sighted policy-making at the long-term cost.

Concrete steps to move forward to more transparent negotiations on fishing quotas:

(1) Improve general transparency of the decision-making

- Publishing more detailed results/minutes of Councils of Ministers and the preparatory bodies online;

- Making all scientific and socio-economic evidence used in the preparatory bodies and in the Council negotiations open for public scrutiny;

- Allowing live-streaming of the exchange of views of Councils, in accordance with Article 8 of the Council’s Rules (2009/937/EU), especially for the presentation of the European Commission’s communication on fishing opportunities for the following year and subsequent negotiations of fishing opportunities for the Baltic sea, deep sea and the Atlantic;

- Clarifying whether negotiations of ministers are considered a political agreement (A-item) or legislative act (B-item).

(2) Shield the decision-making process from undue influence of special interest by:

- Not welcoming unregistered lobbyists any longer at the Council. This means that unregistered lobbyists should not be able to get meetings with Permanent Representations of member states and the rotating presidency both in Brussels and “at home”. Unregistered lobbyists should also not have access to the Council premises.

- Publishing all written input by lobbyists in a central location to allow the establishment of an EU Legislative Footprint.

- Allowing the public to monitor that the above principles are respected, the Council by publishing meetings with lobbyists in a similar fashion to the European Commission.

(3) Enhance democratic accountability of the decision-making process by:

- Making Member State negotiation positions and voting public after the negotiations, including reasoning for demanding fishing limits exceeding scientifically advised levels.